We help decision makers

take hard decisions and build public trust

With 95 organizational members and 94 individual members across 55 countries and six continents, involving over 300 people, Democracy R&D is the largest global network dedicated to deliberative democracy and democratic innovation.

The challenge

With outdated tools, eroding public trust and pressure for quick fixes, it’s hard for governments to make wise long-term decisions.

Our approach

We empower diverse groups of citizens to reach informed judgements and share decisions with governments. We achieve this with deep democratic practices such as random selection (sortition) and deliberation. Anyone facing election cannot ignore public opinion. Our models offer something better: public judgment.

Our impact

Our members have helped governments from the local to the global generate trust, understanding, and solutions to some of the most challenging problems. We’re bringing everyday people back into public decision making.

Project

Spotlight

Forum Against Fakes

Digital innovations such as high-speed internet, artificial intelligence, smartphones and social media have dramatically changed the speed, intensity and nature of public communication. These innovations have many positive effects, but they also facilitate the spread of what is known as disinformation. This manipulated or false information makes many people feel uncertain and puts pressure on our democracy.

Community plan: redesigning a street in São Paulo

In partnership with the NGO Fundação Tide Setúbal, randomly selected citizens in a peripheral neighborhood of São Paulo made 12 recommendations about a new design for the main street, as the first implemented action of the “Plano de Bairro do Território Lapenna”. Besides the effectiveness of the deliberation process and achieving consensus on some critical issues for the community, our partners were impressed with the potential of mini-publics to engage ordinary citizens who had never participated in other civic initiatives.

Citizens‘ Assembly on Democratic Reform

During two weekends in September 2019, a diverse group of 160 randomly-selected Germans discussed how Germany can overcome declining voter turnout and dissatisfaction with politics – especially among low-income, and educationally disadvantaged citizens. Their 22 recommendations included complementing parliamentary systems with elements of citizens’ participation and direct democracy.

Our reach

We are 189 organizations and individuals in 55 countries on 6 continents. And growing…

Our reach

We are 189 organizations and individuals in 55 countries on 6 continents. And growing…

To view our members across organizations and individuals

Select a country

-

99

Members worldwide

-

4

Africa

-

10

Asia

-

5

Australia

-

55

Europe

-

7

Latin America

-

18

North America

Testimonials

Emmanuel Macron

Nicola Sturgeon

“Against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic, Assembly members have learned from experts and each other, developing ambitious recommendations for Scotland to change to tackle the climate emergency in an effective and fair way".

Peggy Flynn

California on the Petaluma Fairgrounds

Advisory Panel

"Lottery-selected democracy guarantees representation of many identities rather than relying on those who have the time, confidence, and resources to show up. And it fundamentally shifts power to communities".

Micheál Martin

“The new Citizens’ Assemblies will provide a means by which everyday people, who normally don’t get the opportunity to be involved in policy development or legislative proposals, to make a very real and direct contribution to the State’s response”.

António Guterres

“The Global Citizens’ Assembly for COP26 is a practical way of showing how we can accelerate action through solidarity and people power”.

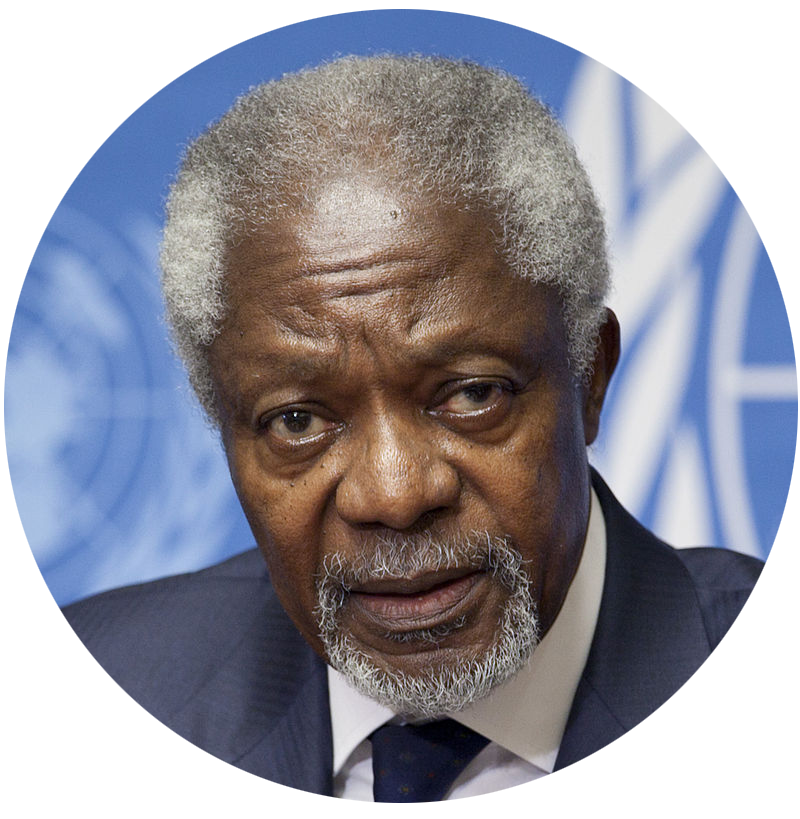

Kofi Annan

“Parliamentarians would no longer be nominated by political parties, but chosen at random for a limited term. This would prevent the formation of self-serving and self-perpetuating political classes disconnected from their electorates”.

Ursula von der Leyen

"The citizens' panels that were central to the Conference (on the Future of Europe) will now become a regular feature of our democratic life".

Mike Russell

Lisa Marie Barron

in Canada

“Citizens' assemblies have considerable legitimacy and public trust because they are independent, non-partisan, representative bodies of citizens".

Claudia Chwalisz

“These new institutions embody the potential of democratic renewal. Many of the criticisms against deliberative democracy are similar to those that were first levelled against universal suffrage in another age".

Nicole Curato

and Lucy Parry

Dark Times

“Deliberative democracy may have been the punching bag of those who remain sceptical of the virtues of participation governed by reason, but it has also been a beacon of hope for visionaries who keep on asking how we can make democracy better”.

Get involved

Learn from our members’ projects and experiences – as well as an inspiring list of books, videos and iconic articles.

Collaborate

We work with governments from the local to the global level. It all starts with a confidential conversation.

- team@democracyrd.org

- +00 000 00000 000000

Fill up the form to register

Strategic Partnerships