01

Living Guidebook

Deliberation on Difficult Issues

The living guidebook is the result of several virtual and face-to-face workshops and activities with members of the Democracy R&D Network. In these activities and workshops, members of the network shared their different perspectives on deliberation on difficult issues.

It covers the topic of deliberating on ‘difficult issues’. Isn’t that what deliberation is for?

Yes, however, what we’re discussing in this living guidebook are the challenges of deliberating on issues, or in contexts, that force organisers and practitioners of a deliberation to modify their practice beyond the usual approach. In these circumstances, design and process decisions are made to accommodate or defuse things like deep polarisation, mistrust or anger because of the risk they pose to the successful implementation of a deliberation.

For example, an organisation is hosting a deliberation on the topic of vaccine mandates in a given community. In this community, significant portions of the community feel very strongly about this issue. What adaptations will need to be made to the design and implementation of a public deliberation in these circumstances? Is there necessary work prior to the deliberation phase? Can we even deliberate in this context?

This living guidebook aims to help answer these questions with reference to the few real-world examples of deliberation on ‘difficult issues’.

The living guidebook is written for practitioners and organisers of minipublics and other forms of deliberation. It is the result of several virtual and face-to-face workshops and activities with members of the Democracy R&D Network. In these activities and workshops, members of the network shared their different perspectives on deliberation on difficult issues. Research was done into existing examples of deliberation on difficult issues; resources and learnings from relevant adjacent fields such as conflict management, dispute resolution and risk communication; and theorising about the possible weaknesses “difficulty” poses to the various stages of a deliberation.

This guide was developed under the leadership of the Difficult Issues Committee of Democracy R&D, spearheaded by Kyle Redman from New Democracy. The project also benefited from the valuable contributions of Aviv Ovadya, Canning Malkin, Claire Mellier, Damir Kapidžić, David Schecter, Debbie Ross, Eva Bordos, Gazela Pudar Draško, Iain Walker, John Badawi, Keith Greaves, Marjan Ehsassi, Nicole Hunter, Santiago Niño, and Susan Lee.

Table of content

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

The word ‘deliberation’ can cover a wide range of situations and concepts.

For this guide, we’re discussing deliberation in the context of deliberative democracy and primarily its use in minipublics. That is where a lot of the experience in the Democracy R&D Network lies and while the guide will be useful for a wide range of processes this allows us to focus our attention on specifics.

Additionally, advice and experiences in this guide will be useful for all kinds of engagement no matter the extent to which they are deliberative because they draw on learnings from other fields such as conflict management, dispute resolution and risk communication.

Deliberation is the process of discussing and debating issues respectfully and inclusively to arrive at a shared understanding and consensus-based decision.

Deliberative democracy takes what is often referred to as the principles of deliberation and applies them to processes of collective decision-making. These processes are commonly referred to as minipublics, citizens’ assemblies, and more.

Deliberative democracy is an increasingly popular approach to resolving complex problems in communities around the world. This is because it specialises in finding common ground amongst a representative mix of people on trade-offs that address a given public issue. By giving people lots of information, time to consume it, incentives to do that, and meaningful influence over any final decision, deliberative processes like citizens’ assemblies equip everyday people with the capability to find agreement on challenging problems. There are countless examples of these processes resolving hard problems – that’s what they do.

However, some issues or contexts are inherently more difficult to deliberate on than others. These circumstances often involve deeply held beliefs, values, and emotions, and can be polarising or controversial. They might occur in complex contexts with historical polarisation that transcends generations. So, while deliberative democracy might specialise in addressing difficult issues, some issues pose a challenge to the way we do deliberative democracy that makes them truly difficult.

Deliberative Democracy

Principles of Deliberation – Application to Collective Decision-Making Processes

Processes

Minipublics

- Citizens' Assemblies

Characteristics

Resolution of Complex Problems

- Finding Common Ground

- Providing Abundant Information

- Time for Information Assimilation

- Incentives for Participation

Challenges

Inherently Difficult Topics for Deliberation

- Deeply Held Beliefs, Values, Emotions

- Polarization and Controversy

- Complex Contexts with Historical Polarization

Difficulties in the Deliberation Process

- Unique Challenges for Deliberative Democracy

Fundamentally, citizens’ assemblies take a representative sample of the population chosen by lottery and provide them with sufficient information, time, resources and support to facilitate their finding of common ground on recommendations that address a posed public policy issue.

That process—recruiting people, building an understanding, defining the problem, developing ideas, drafting recommendations, and finding agreement—is a complex and well-honed process that facilitation teams professionally (or sometimes internal to the organiser) deliver. It is logical and each conversation, exercise and meeting build upon one another to eventually arrive at the final set of decisions.

Each citizens’ assembly is different, sometimes completely so. This is because they are geographically, jurisdictionally, and culturally bespoke processes that respond to the needs of each context. Yet, there is a core set of deliberative principles that unite each deliberative process. These principles are outlined in documents such as the OECD’s Good Practice Principles for Deliberative Processes for Public Decision Making, the UNDEF Democracy Beyond Elections Handbook, MosaicLab’s Facilitating Deliberation: A Practical Guide (this guide in particular is referenced throughout this document as facilitators play a key role in managing difficulty throughout a deliberation, it is an essential resource), DemocracyNext’s Assembling an Assembly Guide and more.

They include:

Purpose

The assembly has a clear remit or problem that it is asked to address.

Influence

The assembly has a public and meaningful level of influence over the decision.

Representativeness

Membership of the assembly is representative of the population and chosen by lottery.

Information

Sufficient and diverse sources of information are made available.

Time

Sufficient time is provided to learn and deliberate.

Group deliberation

The assembly finds common ground on decisions through equitable discussion and deliberation.

Transparency

The process is open and publicly accessible.

These principles translate into practice in a number of different ways but the above guides all generally describe the same process because they aim to fit the journey of deliberation into as efficient yet rigorous a timeframe as possible.

These process steps are:

Establish the process with the convening authority/organisation

Hire independent facilitators to deliver the citizens’ assembly

Provide the citizens’ assembly with a clear level of influence

Decide on a clear remit for the citizens’ assembly

Recruit a representative mix of people by democratic lottery

Provide the assembly with sufficient information, and access to expert speakers including the ability to nominate their own

Allow enough time for the assembly to learn, deliberate and find common ground on recommendations

Facilitate deliberation and dialogue on the issue,

Find common ground on a set of recommendations that respond to the remit in a free way

Deliver the recommendations report to the decision-maker

The decision maker reports back to the assembly on recommendation acceptance and plans for implementation

This general process and the more detailed best practices that are described in the above guides are what we might call “doing deliberation in normal conditions”. The approach naturally accounts for the challenges inherent to asking a room of random people to find agreement on solutions to complex problems.

There will be situations where some of these principles are compromised due to constraints such as low budgets, tight timeframes, and a low level of influence. These situations make running an assembly challenging because they are logistical constraints that impact the organiser’s ability to meet best practice standards, compromising the potential for the assembly to meet expectations that might be high. It’s important to manage expectations to the reality of your situation. There is no problem running a deliberative engagement process that does not meet all of these principles to the maximum extent possible—this is still above and beyond usual practice for community engagement—issues arise however when you set expectations that cannot be met.

One way to manage deliberating in these settings is to view the principles as dials that can be turned up or down. In situations where you are time-constrained, you will need to reduce the time spent deliberating to fit within a given window of time. This will impact what you can spend your time on and so you will need to also reduce the scope of the discussion to account for the limited amount of time you have for learning, deliberating and decision-making.

Similarly, you might want to make your engagement more deliberative but cannot afford to run a multi-day assembly or pay participants to participate. In these settings, you might apply stratification and diverse information inputs to a self-selected group to help improve the deliberative qualities of the engagement without describing it as a citizens’ assembly.

What can make deliberation truly difficult is when the issue itself or the context of the deliberation poses a risk to the integrity or well-functioning of any of the steps of a deliberation.

For example, an issue might have a very high degree of polarisation in a community that results in the potential for a significant skew to the recruitment of participants which would jeopardize the representativeness of the recruitment. This poses a challenge for deliberation because one of the core principles of deliberation is that the assembly is representative of the wider population. Therefore, organisers of the citizens’ assembly will need to adjust their process to account for this difficulty. They might need to build relationships with key stakeholders in the different polarised groups and develop strategies for reaching people or counteracting attempts to manipulate the recruitment process.

These difficulties can take a number of forms but there are some broad categories of difficulty.

We can categorise difficulties by the impact they can have on the deliberation.

People will not be able to deliberate

People will not be able to deliberate

People will not attend

People will not attend

People will not trust the organiser

People will not trust the organiser

People will not trust the process

People will not trust the process

People’s safety will be at risk

People’s safety will be at risk

We can also categorize by the sources of the difficulty.

These challenges arise when participants are strongly emotionally invested in an issue, which can make it difficult for them to approach the issue in an open or honest manner. This can be particularly challenging when discussing issues such as abortion or euthanasia, which can be deeply personal and emotionally charged.

These challenges arise when participants fundamentally challenge the epistemological foundations of the issue, which can make it difficult or impossible for them to approach the issue at all as their foundational understanding of the issue is incongruent with the framing or assumptions embedded in the deliberation.

These challenges arise when there are power imbalances or historical and cultural contexts that affect how participants engage in the deliberative process. This can be particularly challenging when discussing issues such as indigenous rights or post-conflict discussions, which involve deeply entrenched power imbalances and historical injustices. They might involve societal experience of violence or war and include low or non-existent trust between participants or their communities.

These challenges arise when participants struggle to understand or engage with complex technical or scientific information. This can be particularly challenging when discussing issues such as genetics, and artificial intelligence, which involve complex scientific concepts and models.

These challenges arise from the structure of the deliberative process itself, such as the design of the process or the role of facilitators. This can be particularly challenging when designing citizens’ assemblies or other forms of deliberative democracy, which require careful consideration of the structure and design of the process.

We can also categorize by the sources of the difficulty.

Are there issues that are simply “off the table”?

When considering what topics might be deemed undebatable, human rights often come to the forefront. These rights are typically categorised into:

While these rights are generally upheld as universal, the interpretation and implementation can vary greatly, leading to debate over their application rather than their existence.

Who gets to decide that something is “off the

table”?

Determining what is undebatable is in itself a complex issue, influenced by various power structures and disputes. Key determinants include:

Each of these actors contributes to a dynamic and often contentious process of defining the parameters of public deliberation. Understanding this interplay is crucial for any effective citizens’ assembly, as it navigates the complex landscape of political and social discourse.

Difficulty can arise in many contexts and involve a wide range of topics.

Difficulty can arise in many contexts and involve a wide range of topics. Some recent real-world examples include Ireland’s Citizens’ Assembly on Abortion, Citizens’ Assemblies in post-conflict regions such as Bosnia and Herzegovina, the South Australia Nuclear Fuel Cycle Citizens’ Jury, various Citizens’ Assemblies on Climate Change, and deliberation on Reunification in Korea. These issues are often difficult to discuss because they involve fundamental values and beliefs that are deeply held by individuals and communities.

Several difficulties can arise when deliberating in specific contexts. These difficulties may include participant polarisation (not specifically related to the issue), post-conflict situations, ethnic tensions, historical injustices, institutional weakness (trust and legitimacy), institutional capacity (resourcing), authoritarian regimes, social resistance to dissent, and stakeholder sabotage. All of these factors can undermine the effectiveness of a deliberative process, and can also combine to create even more difficult circumstances.

Ireland’s Citizens’

Assembly on Abortion

Bosnia and Herzegovina

Assemblies in post-conflict regions

South Australia

Nuclear Fuel Cycle Citizens’ Jury

Korea

Citizens’ Assemblies on Climate Change, and deliberation on Reunification

Often, issues and contexts intertwine. While some topics are difficult in their own right, political and social contexts can make routine deliberations challenging due to the polarisation they introduce into the room. In this guide, we will not touch on contexts that make the administration of citizens’ assemblies difficult due to common but severe constraints, such as financial, literacy, time, and safety.

A lack of physical safety may be a downstream effect of some of the following issues or contexts but it is generally accepted that, whatever the cause, compromised physical safety of participants raises challenges that fundamentally undermine the safe and genuinely deliberative nature of citizens’ assemblies and must otherwise be addressed before true deliberation can take place.

In general, difficulty arises from polarisation that precedes a deliberation. This section outlines some of these areas:

Issues related to group identity or ethnicity can be difficult to deliberate on. These issues may be emotional and can be tied to past traumas or injustices. In some cases, participants may have experienced violence or discrimination themselves or may have family members who have. These experiences can make it difficult to engage in respectful dialogue and may require special attention to ensure that all voices are heard. Examples here include citizens’ assemblies in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Issues related to post-conflict situations or in post-conflict contexts are difficult to deliberate on. These issues may be emotional and can be tied to past traumas or injustices. In some cases, participants may have experienced violence or discrimination themselves or may have family members who have. These experiences can make it difficult to engage in respectful dialogue and may require special attention to ensure that all voices are heard. Examples here include citizens’ assemblies in Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Issues related to other forms of historical polarisation can be difficult to deliberate on. These issues may be emotional and can be tied to past traumas or injustices. These experiences can make it difficult to engage in respectful dialogue and may require special attention to ensure that all voices are heard. Examples here include downstream cultural and political impacts from civil conflicts such as the American Civil War.

When individuals hold strongly opposing views on an issue, it can be difficult to find common ground and reach a consensus. This is common when deliberating on values-laden questions – issues that involve fundamental values or identity questions, such as marriage equality, abortion, race or immigration. Deliberating on these issues can be particularly difficult because people’s values and identities are often deeply held and can be difficult to reconcile. An example of this might be polarisation on the issue of vaccine mandates such as in the Citizens’ Panel on COVID-19 in Michigan.

Some issues may face a specific form of polarisation where a claim is made to a separate absolutist source of power that theoretically should be making the decisions according some deliberators such as when religion is involved. This might be similar to the above form of polarisation but with some unique complications because of the way in which it can combine group identity, ethnicity and the nature of some forms of religion.

Political issues can also be challenging to deliberate on, particularly in contexts where there is a high degree of partisanship or polarisation. When participants have strong partisan affiliations or are heavily influenced by political ideologies, it can be difficult to reach a consensus or engage in productive dialogue. For example, Bosnia and Herzegovina Citizens’ Assembly for Constitutional and Electoral Reform.

Issues related to indigenous rights can also be difficult to deliberate on. Indigenous communities may have unique perspectives and experiences that are not fully understood by non-indigenous participants. In addition, historical injustices and ongoing systemic discrimination can make it difficult to engage in respectful dialogue. For example, the South Australia Nuclear Fuel Cycle Citizens’ Assembly.

Issues related to future generations and social change can be difficult to deliberate on. These issues often require participants to think beyond their immediate interests and consider the needs of future generations, sometimes many decades into the future. They may also require participants to grapple with complex ethical and moral questions.

A power imbalance can make deliberation difficult because it can limit the ability of some participants to fully engage in the deliberation process. Power imbalances can occur in various ways, such as through social status, economic resources, or political influence. When one group has significantly more power than another, it can influence the deliberation in their favour and silence the voices of less powerful groups.

One important question to consider when deliberating on difficult issues is whether or not the process can change people’s views.

Research shows that through deliberation, people’s views often change when presented with new information and the personal stories of their neighbours. However, not all issues are created equally when it comes to openness to changing our minds.

If you have identified polarisation or outrage that might impact your deliberation, there may be some work to do before the issue is brought to the deliberation stage.

This work can be complex and time-consuming and getting to the point where you are ready for deliberation may take years or decades depending on the context.

It’s important to note that polarisation does not necessarily need to be “solved” or “dealt with” before a process can begin. Understanding and learning is essential beforehand but during the process polarisation sometimes only needs to be (respectfully) acknowledged and managed.

Mosaic Lab has the following advice

Where people hold polar opposite views, it’s important to gain a deeper understanding of the community’s polarisation before choosing a process (deliberative or otherwise) to deal with the issue. This can be done as part of a wider engagement process of interviewing a range of community members and documenting the different perspectives that people hold on the topic.

“Responding to Community Outrage: Strategies for Effective Risk Communication” by Peter M. Sandman is a seminal work focused on the field of risk communication, especially on how to effectively communicate risks to communities that are upset or outraged.

The book outlines Sandman’s Risk Communication Model, which distinguishes between the technical assessment of risk and the psychological perception of risk. Sandman posits that the level of concern or outrage felt by the public about a particular issue is often influenced more by factors unrelated to the actual, technical risk involved. These factors can include trust in the institution or company communicating the risk, the fairness and transparency of the process, and the degree of control people feel they have over the risk.

Sandman’s main argument is that effective risk communication must address both the technical aspects of the risk and the community’s emotional response to it. He offers a variety of strategies for communicators to better engage with their audiences, aiming to decrease outrage and improve understanding and cooperation. These strategies include being honest and transparent, acknowledging and addressing emotions, listening to and involving the community in the decision-making process, and providing clear and actionable advice on how individuals can protect themselves or reduce their risk.

Here’s a list of key strategies outlined in Sandman:

Acknowledge and validate feelings

Recognize and accept the community's feelings of fear, anger, or frustration. Validating these emotions can build trust and open lines of communication.

Be transparent

Share all relevant information, including what is known, what is not known, and the steps being taken to find out more. Transparency builds credibility and trust.

Listen actively

Engage in genuine listening to understand the community's concerns and perspectives. This involves not just hearing words but also paying attention to non-verbal cues and emotions.

These strategies emphasize the importance of treating the community with respect, understanding their concerns, and communicating in an open, honest, and empathetic manner. Effective risk communication is not just about conveying facts but also about building and maintaining trust.

“Polarity Management: Identifying and Managing Unsolvable Problems” by Barry Johnson introduces the concept of polarity management, which is a framework used to address issues that cannot be solved in the traditional sense but rather managed over time. These issues, or polarities, are interdependent values that exist in a state of tension with each other.

Johnson argues that many of the challenges we face in organizations, communities, and personal lives are not problems to be solved, but polarities to be managed. A classic example of such a polarity is the need for change versus the need for stability. Both elements are essential, and focusing exclusively on one at the expense of the other can lead to failure.

The book outlines a methodology for identifying polarities and demonstrates how to manage them effectively. This involves recognizing the values inherent in each pole, understanding the negative consequences of overemphasizing one pole and developing strategies to leverage the strengths of both poles.

It challenges the either/or thinking that often dominates problem-solving efforts and replaces it with a both/and perspective that embraces complexity and fosters more adaptive and resilient systems. This has applications to many fields but is well suited to deliberation.

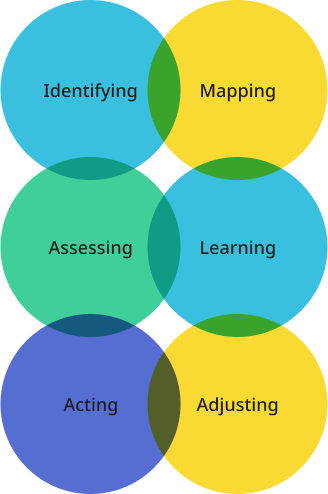

Here’s a summary of the core methodology:

The first step is to recognize that the issue at hand is a polarity to be managed, not a problem to be solved. This involves distinguishing between solvable problems and ongoing polarities that require balance over time.

Once a polarity is identified, it is mapped using a Polarity Map. This tool helps visualize the two poles and their associated values, as well as the upsides of maximizing each pole and the downsides of over-focusing on one to the detriment of the other.

This involves understanding the positive and negative aspects of each pole. The goal is to see the benefits of both poles and the pitfalls of focusing too much on one side. It’s crucial to recognize that each pole has its own strengths and weaknesses and that overemphasizing one pole can lead to negative consequences.

This step involves considering the broader context and learning from others who have managed similar polarities. It’s about understanding how the polarity operates within the larger system and identifying strategies that have been effective elsewhere.

Based on the insights gained from mapping and assessing the polarity, develop action steps that leverage the upsides of both poles while mitigating the downsides. This includes setting specific, actionable goals that balance the needs and values associated with each pole.

Finally, the process involves regular monitoring of the outcomes of the action steps and adjusting strategies as needed. This is a dynamic process, as the balance between the poles may shift over time or with changing circumstances. Continuous monitoring allows for adjustments to maintain an effective balance between the poles.

Polarity Management is a continuous process of identifying, mapping, assessing, learning, acting, and adjusting.

It emphasises the importance of recognizing and valuing the benefits of both sides of a polarity, rather than seeking a permanent solution to what is essentially an ongoing dynamic. By following this methodology, organisations and individuals can navigate complex issues more effectively, leading to more sustainable and balanced outcomes.

A citizens’ assembly can be broken down into several stages. Each stage has specific functions that are vulnerable to difficulty in a variety of ways. This section breaks down each stage.

Wider engagement prior to the deliberation stage

Many deliberations are preceded by some form of wider engagement—processes where any member of the public can provide input on the issue through a range of activities, such as surveys, submissions, workshops, and public meetings.

Interest groups and other stakeholders affected by the issue can be encouraged to provide their input at this stage of the process or through specific stakeholder forums. The findings from this wider engagement can be collated and provided as an information input for the deliberating group and can help inform the design stage.

This engagement fulfils a number of roles. It provides the deliberating group with corroborating information that can confirm or realign their work to ensure they are focusing on the priorities of the wider community. It can help ensure that the views of marginalised or minority groups are expressed in more than one format. It can act as a safeguard against the deliberating group missing anything critical.

Vulnerabilities to difficulty:

- Polarisation can lead to gaming or stacking of the wider engagement.

- The wider engagement might phrase questions or provide information in an offputting way.

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies:

- Use targeted outreach to build relationships with key voices in polarised groups to balance inputs.

- Ask questions that reveal issue position to capture balance of inputs.

- Consult key groups when developing questions.

The beginning stage of any deliberation includes establishing key foundational elements. These include connecting the process to a public decision, allocating time and resources, establishing governance arrangements, and conducting process design in a way that best adheres to established norms and best practices.

Vulnerabilities with examples:

- Issue Polarisation: The process design might unintentionally favor certain viewpoints.

- Complexity: Overlooking key aspects of a complex issue.

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies:

- Engage a diverse group in process design to ensure all perspectives are considered.

- Break down complex issues into more manageable parts for easier understanding and discussion.

Facilitation is a specific skill that requires training, know-how and experience. Its independence from the organisation hosting the process ensures its legitimacy and success.

Vulnerabilities with examples:

- Perceived facilitation biases due to polarisation

- Ethnic Polarization: Facilitator biases or insensitivity towards ethnic issues.

- Post-Conflict: Difficulty in maintaining neutrality in charged post-conflict settings.

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies, with Examples:

- Train facilitators in cultural sensitivity and conflict resolution.

- In the case of the BiH National Citizens’ Assembly, facilitator training was organised specifically around the polarising issues, and also to allow for teambuilding among co-facilitators.

- Employ co-facilitation with facilitators from different ethnic or conflict-affected backgrounds.

Making sure a Citizens’ Assembly will influence public decisions is an important task. The commissioning public authority, institution, or organisation should publicly commit to responding to or acting on recommendations developed by the Assembly promptly.

Vulnerabilities with examples:

- Sovereignty challenges aimed at the organiser

- Lack of trust due to polarisation

- Political Polarization: Decisions of the assembly being disregarded due to political biases.

- Power Imbalance: Influential groups undermining the assembly’s authority.

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies:

- Secure commitments from political leaders to consider the assembly’s outcomes.

- Establish clear, transparent mechanisms for how assembly decisions will be used.

Citizens’ assemblies require a clear question or mandate to which they respond. This ensures the process is focused and actionable.

Vulnerabilities with examples:

- Disagreement over the terms of the discussion due to polarisation

- Indigenous Rights: The remit not adequately addressing or respecting indigenous issues.

- Future Generations and Social Change: The remit failing to consider long-term implications.

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies:

- Consult with indigenous groups when setting the remit.

- Include future scenario planning in the assembly process to address long-term impacts.

How and who will be chosen to be part of the process? There are a wide range of recruitment decisions that will impact accessibility, representation and the overall legitimacy of the process. This is usually done via democratic lottery.

Vulnerabilities with examples:

- Ethnic Polarization: Not achieving a representative mix of ethnic groups.

- Post-Conflict: Recruitment being skewed by ongoing tensions.

- Cultural misalignment: Is it normal for anyone to participate in decision-making?

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies, with Examples:

- Use targeted outreach to ensure diverse ethnic representation.

- Involve peace-building organizations in the recruitment process in post-conflict areas.

Deliberative processes require sufficient time for the group to consider a wide range of information, deliberate and find agreement on recommendations.

Vulnerabilities with Examples:

- Complexity: Insufficient time allocated to understand complex issues thoroughly.

- Issue Polarization: Rushed deliberations may exacerbate tensions.

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies, with Examples:

- Extend the duration of assemblies dealing with complex issues.

- In Bosnia, organisers experienced time constraints but they led to more productive work (without reducing the process below recommendation lengths for a deliberation). However they also took time to allow participants to debate any polarising issues. If this is rushed then the outcome of such deliberations can exacerbate tensions.

- Schedule additional time for sensitive or polarizing topics to allow thorough discussion.

- Consider the need for pre-deliberation work that builds the foundation for a deliberation.

Deliberations require a wide range of information from a mix of sources to ensure that all perspectives have been considered fairly.

Vulnerabilities with Examples:

- Epistemic Conflict: Disagreements over the credibility of information sources.

- Complexity: Challenges in understanding technical or scientific data.

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies, with Examples:

- Provide information from a range of credible, diverse sources.

- Use experts to explain complex concepts in accessible ways.

- Establish a stakeholder group to advise on information sources.

Fundamental to any deliberative process is the ability for the group to discuss the issue and reason with one another over the challenges and trade-offs involved.

Vulnerabilities with Examples:

- Political Polarisation: Inability to engage in productive dialogue due to entrenched views.

- Historical Polarisation: Past traumas affecting current discussions.

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies, with Examples:

- Use structured dialogue techniques to manage polarised discussions.

- Integrate historical context and sensitivities into the dialogue process.

- Use pre-deliberation work to lay the foundation for deliberation on an issue.

- In Bosnia, organisers created an online video resource for participants with expert testimonies on key issues around the topic and on foundations on inclusive deliberation.

Vulnerabilities with Examples:

- Power Imbalance: Certain voices dominate the conversation and development of recommendations.

- Ethnic Polarization: Marginalisation of minority groups.

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies, with Examples:

- Encourage equal participation and actively involve quieter members.

- Use supermajority voting principles for final recommendation adoption (80%)

- Use anonymous feedback mechanisms to capture all voices.

The group delivers its recommendations to the decision-maker who has made a commitment to act on the recommendations in some way (publicly respond, or implement recommendations in full).

Vulnerabilities with examples:

- Political Polarisation: Recommendations being ignored due to political biases.

- Complexity: Misinterpretation of complex recommendations.

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies, with Examples:

- Facilitate direct interactions between the assembly and decision-makers before and after recommendations are developed.

- Simplify complex recommendations into clear, actionable items (focusing on clarity of intent rather then prescribing detailed actions).

Building trust in the process between assembly members, decision-makers and the wider public requires complete transparency,

Vulnerabilities with examples:

- Issue Polarisation: Public scepticism about the assembly’s integrity.

- Historical Polarisation: Lack of trust based on historical experiences.

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies, with Examples:

- Regularly publish updates and methodologies used in the assembly.

- Host public forums to explain the process and address concerns.

The sponsoring organisation needs to be held accountable to the commitments it makes at the beginning of the process. This might happen through reporting back at regular meetings or by publicising their updates the the broader community.

Vulnerabilities with examples:

- Power Imbalance: Accountability being skewed in favor of powerful groups.

- Post-Conflict: Difficulty in establishing trust in accountability mechanisms.

Mitigating Techniques/Strategies, with Examples:

- Establish independent oversight mechanisms for accountability.

- Involve international observers or mediators in post-conflict settings.

Dealing with polarisation and outrage in an online deliberation—while not impossible—may be more difficult than in a face-to-face meeting.

Body language and facial expressions are easier to read when face-to-face and can reveal participants’ willingness to communicate and build relationships. Community division over an issue may have been present for a long time, so an online discussion will not be the most effective method for resolving the issue.

If you have to hold to a very polarised discussion online then

consider these simple approaches to get the most out of it:

a

Keep the process simple.

b

Give lots of time for expressing concerns.

c

Slow down and create several short sessions where people can think and discuss before coming to any final positions.

Ideally, this polarisation will be identified in a pre-deliberation phase (possibly during the wider engagement process or during stakeholder consultations in the design phase) so that a range of solutions can be explored, such as stakeholder negotiations, before the issue reaches the deliberation stage. However, in some cases, highly emotional polarisation and outrage will emerge during a deliberation and facilitators may need to put the deliberative process on hold to avoid having the ‘fight’ play out in the room.

In these situations, MosaicLab recommends the following steps, which are based on their experience, discussions with other leading facilitators and several frameworks for dealing with polarisation and outrage.

Understand the polarity in the community

Interview a wide range of people to understand the issues and collect all the perspectives that people hold in relation to the topic. This work may have formed part of the sponsoring organisation’s wider engagement phase prior to deliberation. However, in our experience, it is important that as independent facilitators we test this information by undertaking further interviews. It is critical that the facilitators understand the willingness of the key parties to work together to resolve the issue.

Share and understand different perspectives

The deliberators should be encouraged to explore different perspectives on the issue, including those of other group members, relevant interest groups and possibly some experts. A significant amount of time will be needed for sharing experiences and it’s important that the group does not move on to the next step until everyone understands one another’s perspective.

The relevant fundamental framework for this process is that emotion is explored before hard information or data are considered. People do not hear or take in information while they are holding high levels of emotion. They need to express this emotion before experts are invited to speak. We recommend starting this process by hearing from the least powerful group first until they say they feel heard and then moving on to the other groups or stakeholders. This process allows the participants to frame the polarity and understand the different positions held in the community in relation to the topic. Proceeding to the next step should only happen when the group agrees to do so.

Explore the shared values that underlie different groups’ positions

The next step is critical for working out if it will be possible to find common ground and achieve some form of resolution. Group members should be invited to identify and explore the values that underlie their different positions on the topic. This will take time and it can be useful to think about different sets of values. If two sets of values are seen as being held in two circles, can those circles be overlapped like a Venn diagram to find common ground? Or are they completely distinct and separate sets of values?

Gateway conversation and decision

Once participants have explored any shared values, it will be time to make a decision about the group’s capacity to resume the deliberation. That is, whether they will be able to consider information, collaborate with each other and jointly develop recommendations. Ideally, the group will make this decision, however, in some cases, the sponsoring organisation and facilitators will be in a better position to make this judgement.

Case studies

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

To view the case studies

Select a country

-

3

Members worldwide

-

1

Australia

-

2

Europe

Resources

Lorem ipsum dolor sit amet, consectetur adipiscing elit, sed do eiusmod tempor incididunt ut labore et dolore magna aliqua.

Facilitating Deliberation: A Practical Guide by MosaicLab

This guide is designed to be an all-access journey into the world of facilitating public deliberations. Authored by MosaicLab directors Kimbra White, Nicole Hunter, and Keith Greaves, the guide draws from their collective experience in delivering 39 deliberative engagement processes. The book is filled with insider secrets, lessons learned, and

Facilitator’s Guide to Participatory Decision-Making by Sam Kaner

This guide is a practical resource for anyone looking to involve groups in collaborative decision-making processes. It offers strategies for creating inclusive environments that encourage open dialogue and collective action, which are essential for managing outrage and engaging stakeholders effectively.

Polarity Management: Identifying and Managing Unsolvable Problems by Barry Johnson

This book introduces the concept of polarity management, which is a framework used to address issues that cannot be solved in the traditional sense but rather managed over time. These issues, or polarities, are interdependent values that exist in a state of tension with each other.

Responding to Community Outrage: Strategies for Effective Risk Communication by Peter M. Sandman

A seminal work focused on the field of risk communication, especially on how to effectively communicate risks to communities that are upset or outraged.

Dialogue and the Art of Thinking Together by William Isaacs

This book focuses on the importance of dialogue in resolving conflicts and building understanding between groups. Isaacs provides a framework for creating conversations that foster mutual respect and understanding, which is crucial for effective outrage management and community engagement.

The Dynamics of Conflict Resolution: A Practitioner’s Guide by Bernard Mayer

Mayer’s work offers insights into the nature of conflict and practical strategies for conflict resolution. It emphasizes understanding the underlying interests and needs of parties involved in a conflict, which is essential for managing outrage and engaging communities.

Crucial Conversations: Tools for Talking When Stakes Are High by Kerry Patterson, Joseph Grenny, Ron McMillan, and Al Switzler

This book provides techniques for handling high-stakes conversations effectively, a skill crucial for managing outrage and engaging with communities on sensitive issues.

Comments and contributions

Leave your comments or contributions to this guide

Explore more

Discover Our Living Guide 2

South—North Learning (SNL)

The living guidebook is an innovative tool designed to foster mutual learning within the Democracy R&D.

Discover Our Living Guide 3

Institutionalization

This living guidebook is about incorporating civic lottery, deliberation, and “rough consensus” (and related democratic innovations) into political systems as ongoing practices (not just one-off events) – often called “institutionalization.”