03

Institutionalization

This living guidebook is part of the New Frontiers of Deliberative Democracy project

What is this guidebook about, and why does it matter?

This guidebook is about incorporating civic lottery, deliberation, and “rough consensus” (and related democratic innovations) into political systems as ongoing practices (not just one-off events) – often called “institutionalization.” Compared to only conducting one-off deliberations, institutionalization can enable permanent, structural improvements in democracy, including:

- The ability to address many more tough issues

- The ability to do so more easily, effectively, and efficiently

- An important and powerful role for citizens beyond voting

- Greater public trust in government and the democratic process

Who is this guidebook for?

This guidebook is designed for advocates, practitioners, civil servants, academics, funders, independent thought leaders, and journalists who are seriously interested in making these practices core parts of how democracy works.

How might this help me?

- You will be informed about more options for institutionalization (ones that have been implemented, and promising proposals which have not been implemented yet).

- You will have some useful methodological guidance.

- At the end of the day, you will be more successful at institutionalizing deliberation than you probably would have been without this guidebook.

How might this help me?

- You will be informed about more options for institutionalization (ones that have been implemented, and promising proposals which have not been implemented yet).

- You will have some useful methodological guidance.

- At the end of the day, you will be more successful at institutionalizing deliberation than you probably would have been without this guidebook.

What does this guidebook contain?

There are three sections to this guidebook. The first section talks about what deliberative democracy is and why it matters. It also lays out the kinds of problems with democracy that deliberative democracy can solve – especially if it is institutionalized.

The second section presents options for change. These include case studies about examples of institutionalization. It also includes promising proposals that have not yet been implemented.

The third section is about making institutionalization happen. It includes reflections about embedding deliberation in governments, a set of guidance questions about stakeholders, and a “map” of three possible paths to institutionalization: legislation, government decisions, and binding referenda.

Who developed this guidebook?

This guide was developed under the leadership of David Schecter, with active participation from Felipe Rey, Kyle Redman, Susan Lee, and Canning Malkin. It also benefited from the valuable contributions of Baogang He, Cécile Molle, Claire Mellier, Cynthia Mbamalu, Emma Fletcher, Emily Jenke, Iain Walker, Jane Mansbridge, Jonathan Moskovic, Louise Humblet, Lyn Carson, Melisa Ross, Nicole Curato, Olaniyan Sanusi, and Terrill Bouricius.

A final note

This document is intended to be a “living guidebook.” We intend to update the guidebook and add content over time, as many people accumulate experience with institutionalization, develop new models, and find out how they work in practice.

Why institutionalize deliberation?

What is this about?

What is deliberative democracy?

How is it different from other approaches to democracy?

Why do these differences matter?

Disclaimer

- There is no universally agreed definition of deliberative democracy.

- However, within the Democracy R&D network, there is (mostly) agreement on three core elements.

- Each element is an answer to a big question about the design of any political system.

- The “usual answers” in the next slides relate mainly to democratic political systems. However, the three elements could be relevant to any political system.

Three big questions about political decisions

How are decision makers (or other participants in political conversations) selected?

How do they interact?

How do they decide?

How are decision makers selected?

The usual options

The usual options

Preferred option for DD advocates

Preferred option for DD advocates

Advantages of preferred option

Advantages of preferred option

Civic lottery (aka random selection, sortition)

What is it?

Selecting a representative sample of the public, using lottery selection and “stratification” by relevant characteristics (for example, age, gender, income, ethnicity)

What are its advantages?

It produces a diverse group; it produces a representative group (a microcosm of the public; and the selection process is resistant to manipulation.

Important note

Most deliberative democrats don’t think that deliberation is the best form of interaction for all purposes. But we do think that we can’t solve the big problems of democracy without it.

How do they interact?

The usual options

The usual options

Preferred option for DD advocates

Preferred option for DD advocates

Advantages of preferred option

Advantages of preferred option

Deliberation

What is it?

A type of conversation that is informed, open-minded, non-adversarial, and focused on making a decision that could (ideally) work well for everyone.

What are its advantages?

Participants are well informed; incorporates diverse perspectives; not adversarial; produces better decisions.

Important note

Most deliberative democrats don’t think that deliberation is the best form of interaction for all purposes. But we do think that we can’t solve the big problems of democracy without it.

How do they decide?

The usual options

The usual options

Preferred option for DD advocates

Preferred option for DD advocates

Advantages of preferred option

Advantages of preferred option

Rough consensus

What is it?

A form of decision making where the goal is to get as close as possible, given time and resource constraints, to a decision that everyone could support.

What are its advantages?

Produces decisions that could be widely supported, within reasonable time constraints. Often these decisions are better than any options that participants would have advocated before the deliberation.

Important note

Most deliberative democrats don’t think that rough consensus is the best decision making process for all purposes. But we do think that we can’t solve the big problems of democracy without it.

All three questions, and answers

Comparing four approaches to democracy

Additional “elements” that complement the previous three

Multiple bodies for tasks like lawmaking

Combining standing bodies with one-off bodies

Combining civic lottery (for some functions) with self-selection (for other functions)

Combining elected and randomly selected people in deliberation

There are many problems with contemporary democracies. Deliberative democracy cannot address all of them (for example, problems with electoral systems, corruption, jurisdiction boundaries and relationships between levels of government, human rights). But there are some problems that it is ideally positioned to address.

These stand out:

Gridlock - The most difficult decisions are not made.

There is a lack of meaningful participation for the public between elections.

Public decisions are highly sensitive to public opinion, but not to public judgment.

Representation - Decision making bodies are not very representative of the public.

In many countries, there is a troubling degree of polarization.

Public trust in democracy is low, and declining.

This guidebook is designed to address these problems. In order to do so, three critical aspects of political systems are worthy of note:

a

How participants are selected

b

What kind of conversation they engage in

c

How they make decisions

Let’s take each of those in turn.

a.

How to select the people who decide?

One of the most basic questions in the design of political systems is “Who decides?” If you unpack that question a little, you get something like this – How to select the people who set agendas, develop proposals, and make decisions?

There are three well-known answers:

Elections

Appointment

Self-selection

(an open invitation to anyone who wants to participate)

- You get a group that isn’t very representative of the public.

- You get a group that is less diverse in their perspectives than the public is (and diversity of perspectives is an important factor in good problem solving).

- You get people who are more interested in “winning” than in solving problems for the benefit of the public.

- You get people who “owe things” to the people who helped them get elected or appointed.

- If you have a lot of money and power, it is very possible to influence who is selected.

b.

What kind of conversation they engage in

The well-known modes are:

Debate

Negotiation and bargaining

Opinion giving

(surveys and polling, and typical public meeting process where many people speak, but there is no collaborative problem solving)

What are the problems with these answers?

Debate

Debate

Negotiation and bargaining

Negotiation and bargaining

Opinion giving

Opinion giving

What’s missing is open-minded, informed, collaborative problem solving.

c.

How they make decisions

There are three well-known answers:

Voting

Consensus

What are the problems with these answers?

Voting

Voting

Consensus

Consensus

What’s missing are processes that stimulate critical thinking, explore all possibilities, and allocate sufficient time to analyze and learn together, before working towards a rough consensus that will come as close as possible, given time and resource constraints, to the ideal of a solution that everyone can support.

Options for change

Case Studies

Case 1

Madrid Observatory: solving direct democracy's problem with agenda setting

Author: Susan Lee

The Observatorio de Ciudad (OC) was the first permanent chamber of randomly selected citizens at the city level in Europe. Its origin story begins in the aftermath of the 15M movement, one the biggest popular mobilizations against austerity policies in Spanish history. In May 2015, Ahora Madrid took power in the city administration, ending 24 years of rule by Spain’s center-right party in the capital. The merger party was composed of a coalition of progressive actors, many from 15-M, who converged around the agenda of participatory reforms…

Case 2

Mongolia constitutional deliberative polls: deliberation mandated before constitutional change

Author: Susan Lee

In December 2015, a stratified random sample of 317 Mongolians gathered in the capital city Ulaanbaatar to participate in a Deliberative Poll on major infrastructure projects proposed in the city master plan. The Ulaanbaatar Deliberative Poll, the first of its kind in Mongolia, initially came about through chance encounters between Gombojav Zandanshatar, a former Mongolian MP, Ulaanbaatar’s then-mayor Erdeniin Bat-Üül, and Jim Fishkin, the founder of Deliberative Polling. In 2015, the Deliberative Poll was commissioned and implemented by the Capital City Governor’s Office with support from the Stanford Deliberative Democracy Lab and The Asia Foundation.

Case 3

Agora party: a political party dedicated to deliberative democracy

Author: Susan Lee

Agora is a political party founded in 2018 that holds one seat in the Brussels Regional Parliament (2019-2024). Though taking the form of a political party, Agora identifies as a “social movement.” Distinct from traditional parties, its single programmatic aim is to institutionalize a permanent citizens’ assembly with binding power. The Agora MP’s two mandates—conveying recommendations of a citizens’ assembly and advocating for citizen participation within Parliament—service this goal. As Pepijn Kennis, Agora’s first elected MP puts it, the original motivating logic was, “Let’s go and get that seat because it gives us the human and financial resources to organize these assemblies,” as well as a formal voice to insert citizens’ recommendations into Parliament.

Case 4

Toronto standing panels

Author: Canning Malkin

In 2015, then-city planner of Toronto Jennifer Keesmaat called for the establishment of a sitting citizens’ panel to review and comment on major planning initiatives. Keesmaat was familiar with citizen participatory events at the time and believed that her department’s work could lend itself well to public engagement. This was not the first standing citizens’ panel that Toronto, nor the City Planning Division, had implemented. Prior to the Planning Review Panel, the city had held what was called the Design Review Panel, an opportunity for architects to offer their expert insight and advice to the city.

Case 5

Convention on the Future Armenian: representing an international diaspora

Author: Canning Malkin

The Convention of the Future Armenian is unique in a number of ways: its topic focused on identity and culture rather than a political issue; it included people of Armenian culture from across the world and sought to be reflective of the global Armenian population (which therefore offered unique applications of sortition and ideals of representativity); and its own definition of institutionalization relied on the idea of permanence rather than embedding itself into a governmental or otherwise decision-making body.

Case 6

Ostbelgien: standing agenda council plus one-off citizens' assemblies

Author: Canning Malkin

On September 16, 2019, 24 randomly-selected residents of West Belgium were assembled to decide on the topics of the first institutionalized and permanent deliberative body in the regional government. As participants of the first Citizens’ Council, they represented the beginning of the implementation of what is now called the Ostbelgien Model. This model has since produced numerous Citizens’ Assemblies, deliberative bodies that are convened by a group of citizens and responsible for proposing policy recommendations on a topic chosen by that same group of citizens.

Case 7

Victoria Local Government Act: requiring municipal deliberation on four critical municipal policy documents

Author: Canning Malkin

In 2020, Local Government Victoria decided to review their existing Act (the state’s mandate which its government updates periodically). One minister, Natalie Hutchins, who was the Minister for Local Government, Industrial Relations, and Aboriginal Affairs at the time, had championed deliberative processes as early as 2016. The Greater Geelong City Council began implementing citizen participation in 2016 when the Victorian Parliament voted to dismiss the City Council after an independent investigation. Because of the political shake-up, the Parliament committed to consulting the community in the restructuring of its local government. A citizens’ jury was called by Natalie Hutchins, Minister for Local Government.

Case 8

Institutionalization of Brussels deliberative committees: mixing politicians and citizens

Author: Jonathan Moskovic

Note: We have included two perspectives on the Brussels Mixed Legislative Committees: one from the civil servant side, and the other from the operational. Here, Jonathan Moskovic speaks to his experience as a member of the civil servant team that designed the Committees.

In 2019, the Brussels Francophone Parliament became the first legislative chamber in the world to create “mixed” legislative committees that included elected politicians and randomly selected citizens. This piece tells the story of how this came to be, where it stands now, and what’s next.

Case 9

Institutionalizing deliberation in China

Author: Baogang He

In the last three decades, China has witnessed the development of consultative and deliberative institutions (He, 2006).An increasing number of public hearings have provided people with opportunities to express their opinions on a wide range of issues, such as the price of water and electricity, park entry fees, the relocation of farmers, the conservation of historical landmarks, and even the relocation of the famous Beijing zoo, to name a few (Zhongzhao, et al., 2004).

Options for change

Guidance questions

This section contains an order of questions that is intended to provide some useful guidance for people who are designing a way to institutionalize deliberation by randomly selected samples of the public- for a particular place, or a model that could be adapted in multiple places.

The section is intended to make it easier to go through a design process, and also to document the thinking that went into a design, so that the design is easier to critique and there can be more learning from the design process.

An early version of these questions was developed by David Schecter for the IPDD (Institutionalizing Participatory and Deliberative Democracy) project in Scotland, authorized by the Scottish government and led by Doreen Grove, Head of Open Government for Scotland. Later, the questions were further elaborated to incorporate feedback from members of the Democracy R&D network.

This is a work in progress, as is the whole living guidebook. As more people have experience with institutionalization, we will learn more about what works, and about what guidance is most useful. In particular, we are interested in developing guidance for the implementation and evaluation stages of institutionalization, which are not yet included.

No one involved in developing this section thinks that these questions in this order are right for every situation. In fact, they will probably not be completely right for any situation. However, we think that they can provide a very useful “starting point,” compared to “starting from a blank page.”

following topics:

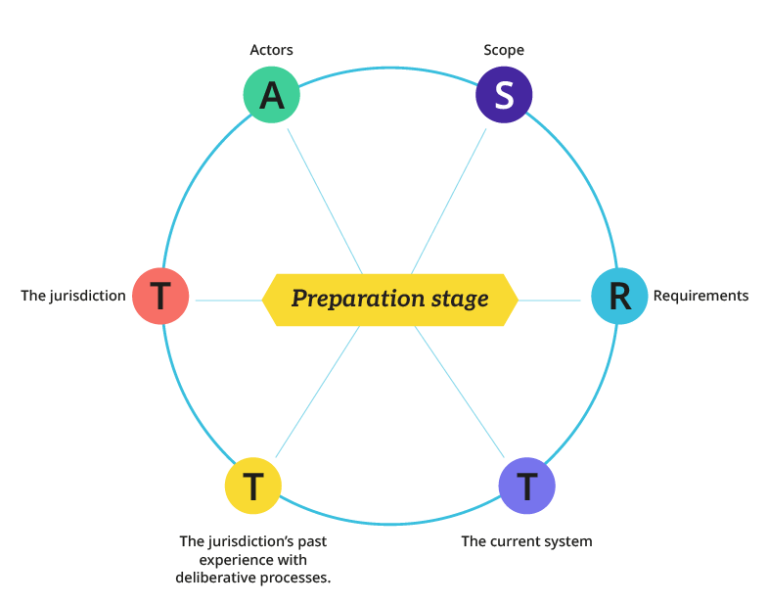

Preparation stage:

Design stage:

For each of these topics, the sections below contain a sequence of useful questions to consider. These are not intended to be a perfect fit for any particular project. Instead, they are intended as a useful starting point for creating an order of questions that does fit a particular project.

This order of questions was chosen carefully, because in a number of cases, the answers to one question will greatly influence the answers to a different question. For example, in the preparation stage, decisions about requirements will depend on decisions about actors, which in turn will depend on decisions about jurisdictions. And in the design stage, decisions about how to allocate roles between bodies will depend on decisions about which functions and/or categories of decisions are within the scope of the design.

However, this sequence should not be followed rigidly. In practice, a team will “jump back and forth” within this order. That is fine, as long as everyone is clear about the dependencies between different decisions.

Making institutionalization

happen - what does it take?

This section is about what it takes to make institutionalization happen, successfully.

The first piece, “Embedding Deliberation into Governments and Public Institutions” by Doreen Grove, discusses the different roles that governments can play in institutionalization, requirements for success, common obstacles, and some promising strategies.

After that, there is a set of questions for planning an advocacy campaign – and after that, there is a “strategy map” that identifies three routes for institutionalizing deliberation: legislation, executive/government decision, and binding referendum. For each path, the map describes a chain of requirements, and also identifies some possible obstacles and strategies to overcome them.

Like the guidance questions in part two, these documents are not intended to precisely fit any particular jurisdiction or campaign. Instead, they are intended as a generic “starting points” for figuring out what will work best in a particular place, for a particular purpose, at a particular time.

Embedding Deliberation into Governments

and Public Institutions.

Recognition of the value of high-quality participation, particularly deliberative formats, is growing around the world. Few are unmoved after observing the intense concentration and animated discussion between a hundred or so randomly selected members of the public during a citizens’ assembly. Participants gain by experiencing a forum where they are pushed, supported, and trusted to seek shared solutions to a tricky problem. The commissioning organisation does too by the common sense of purpose that such an engagement develops. Done well, citizen deliberation is a method of solving societal problems with much to recommend it. But a successful outcome is not the assembly itself. Rather, it is in ensuring the recommendations of the assembly are able to improve the policy or practise that they were designed to address.

In this piece, we define what we mean by institutionalising deliberative democracy, and why embedding this practice into public institutions can support. We also identify risks, and suggest reasons why despite being an effective method it remains extraordinarily difficult to achieve at a systems level and even harder to maintain.

- Civicus Monitor. n.d. Monitor Tracking Civic Space in this link

- Deliberative Democracy Digest. 2022. Risks and lessons from the deliberative wave in this link

- Gabriele Abels, Alberto Alemanno, Ben Crum, Andrey Demidov, Dominik Hierlemann, Anna Renkamp & Alexander Trechsel. 2022. Next level citizen participation in the EU Institutionalising European Citizens’ Assemblies in this link

- OECD. 2021. Eight ways to institutionalise deliberative democracy in this link

- OECD. 2022. Building Trust and Reinforcing Democracy in this link

- Scottish Government. 2022. Report of the Institutionalising Participatory and Deliberative Democracy Working Group in this link

- Scottish Government. 2023. Institutionalising Participatory and Deliberative Democracy working group recommendations: Scottish Government response in this link

Advocacy Questions

Navigate the mind map by clicking on the numbers to see more information

Navigate the mind map by clicking on the numbers to see more information

Explore more

Discover Our Living Guide 1

Deliberation on Difficult Issues

The living guidebook is the result of several virtual and face-to-face workshops and activities with members of the Democracy R&D Network.

Discover Our Living Guide 2

South—North Learning (SNL)

The living guidebook is an innovative tool designed to foster mutual learning within the Democracy R&D.